The Tragic Body

Tragedy is a bloody business, its characters stabbed, poisoned and torn to pieces, their mangled remains carried out into the sunlight to be mourned. But that’s not the sort of ‘body’ we’re talking about here. Instead, we’re thinking about the walking, talking, breathing, sweating bodies of actors on stage; one of Athenian tragedy’s most important innovations.

Before the emergence of tragedy (sometime in the sixth century BCE) performers might sing hymns to the gods, or dance in their honour, but putting on a mask and actually pretending to be a god, or a hero, or a young girl was something new. Brand new theatrical technology!

Ancient tragedy was hugely physically-demanding. Its performers wore masks covering their faces, which meant they had to act with their whole bodies, using each muscle and movement to convey emotions we’re now more used to see flickering across the faces of actors. And performers in the chorus had to work even harder, singing and dancing a series of ‘turns’ that commented on the play’s action, and praised the city’s gods.

Sadly, this is a lost tradition. There’s no surviving scrap of choreography or music that we can confidently say belongs to these ancient choral dances. But the idea of using the expressive, moving body to help tell the stories of tragedy has inspired performers ever since ...

Scholars and Scandals

In ancient Rome, gifted dancers and mimics would re-enact the tales of tragedy, with one performer silently playing all the roles - the world’s first ‘pantomime’. Meanwhile, Seneca was writing Latin versions of Greek tragedies, but despite much scholarly debate we don’t really know whether his texts were meant to be staged, or whether they were private, poetic entertainments for a wealthy elite. As early as the first century CE, the textual and the physical elements of tragedy were already drifting apart.

This separation between words and bodies continued throughout later European history, with tragic poetry becoming an intellectual challenge for schoolboys and scholars, while the physical life of tragedy provided the material for more provocative entertainments. In the eighteenth century, society ladies scandalised respectable opinion by participating in elaborate charades where they dressed as figures from ancient tragedies - their risqué draperies leaving little to the imagination. A century later, such spectacles had begun to influence the popular London stage, where shapely models struck poses inspired by nude classical statues, and quick-talking actresses starred in burlesques of ancient plays, their skimpy costumes designed to show as much leg as possible. Think Kylie Minogue as Aphrodite!

Modern Movers and Shakers

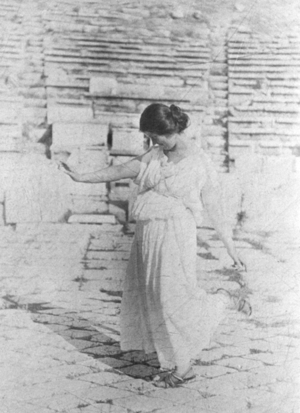

Only in the early twentieth century did the physical performance of ancient tragedy begin to be taken seriously again. At first, it was dancers who led the way. Tired of being stereotyped as pretty nitwits on their toes, groundbreaking modern dancers like Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham invented new steps and styles. Throwing away their ballet shoes and dancing barefoot, preferring loose tunics or dramatic robes to stiff tutus, they modelled their movements on ancient vase-paintings, made ancient tragic heroines the central figures in their ballets, and pioneered a revolution in dance.

Radical change was also afoot elsewhere. In 1931, a young actor and director saw a troupe of Balinese dancers performing in Paris. Stimulated by this experience, Antonin Artaud wrote a manifesto demanding a new sort of theatre, where actors would make their bodies work as hard as those of dancers. Since Artaud, the physical process of performing tragedy has become a concern for directors and actors all over the world, who have probed the connections between the breath we draw in, the muscular shaping of that breath into the words and songs of tragedy, and the appearance and motion of the tragic performer’s body.

For instance, in Poland director Wlodzimierz Staniewski trains his performers in ‘musicality’; the ability to respond deeply and instinctively to the rhythmic impulses of music and song. Gardzienice Theatre re-embody images and gestures from Greek paintings and sculptures to create intense, fast-paced and exhilarating versions of ancient drama.

And the Dance Goes On ...

There’s lots we may never know for sure about the physical performance of tragedy in ancient Athens. But over the millennia Greek tragedy has presented an exciting opportunity for actors and dancers to experiment with different ways of re-imagining this lost tradition. Scandalous or solemn, the bodies of ancient tragedy have rarely been off the stage since the sixth century BCE. And they continue to shock, surprise and move us today.

Want to Find Out More?

Hall E. and R. Wyles. (2008) New Directions in Ancient Pantomime. Oxford.

Harrop, S. (2010). ‘Physical Performance and the Languages of Translation’ (232-240) in E. Hall and S. Harrop (eds) Theorising Performance. Duckworth.

Macintosh F. (ed. 2010) The Ancient Dancer in the Modern World. Oxford.

Taplin, O. (2003) Greek Tragedy in Action. Methuen.

Wiles, D. (2007). Mask and Performance in Ancient Tragedy. Cambridge